No way is this a nice doggy.

This is another book that came highly recommended by a youtuber, which should have given me pause, but at the time I didn’t know any better, and if all the books I reviewed here were good, my few readers would probably get bored. It’s hard to be snarky when discussing something that’s well-written and well-executed.

Have to admit, though, the monster Pomeranian on the cover should have been a dead giveaway.

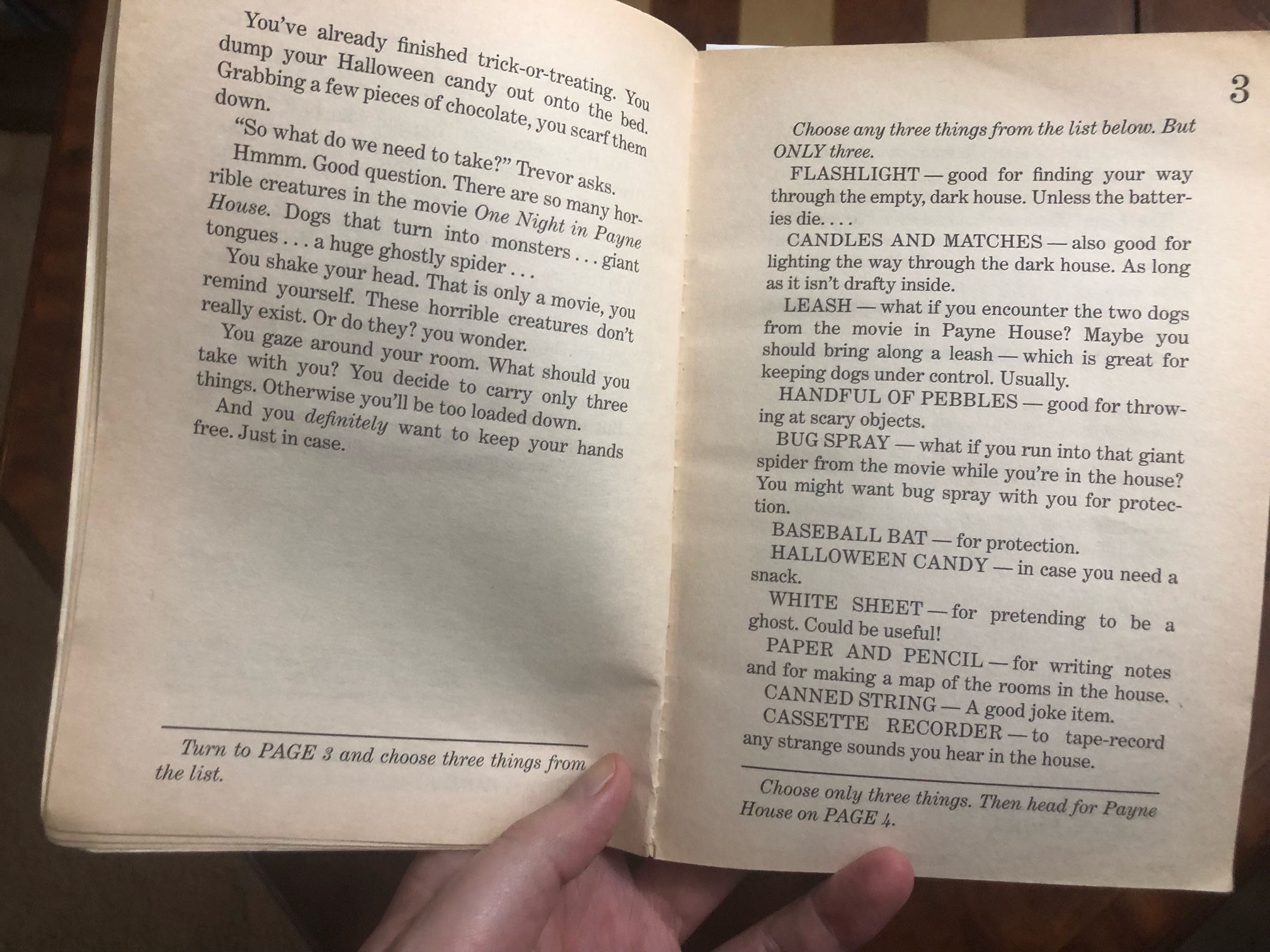

Give Yourself Goosebumps was the gamebook division of the Goosebumps franchise, where longtime readers could finally decide what happened in the story. One Night in Payne House is part of the “ultimate challenge special edition” books, where I guess the big gimmick is the “one true path” design philosophy and maybe inventory keeping, although the inventory aspect itself is really simple: you get to choose 3 items from a grocery list in the first chapter, and most of them are useless.

The premise of One Night in Payne House is a simple haunted house affair. You and your best pal Trevor are almost done with your Trick or Treat run in your neighborhood, and you’ve decided on a dare to enter Payne House, which is haunted to such a degree that it was the subject of a recent movie called One Night in Payne House.

And our hero, the proverbial “you,” will not. shut. up. about. this. movie.

Seriously. Every time you hear, see, or approach anything in this house, our avatar rambles about, “it’s just like in the movie!” Except the rare occasion where he says, “This wasn’t in the movie.” We get more description of what happened in this stupid movie than we do of the actual things happening in the house in real time. Encounter a Pomeranian. Hero spends three paragraphs talking about how the dog in the movie turned into a monster. Then we get one or two sentences about the dog actually becoming a monster.

Right out the gate, this story would have been better without the movie element. Just cut out all references to it and you would just have a mediocre haunted house gamebook. At least then the Pom-Pom dog turning into a monster might have been a surprise.

On the plus side, it starts relatively strong by beginning “in media res,” or “in the middle of the action.” I like stories that start this way, rather than with a long stretch of exposition or setting description. You can always fill that stuff in later as you go. First you gotta hook the reader, usually with a question, like “what’s up with Payne House?” or “why are they going through with this if they’re nervous about it?”

This gets neutralized by the rushed nature of the intro though. That last paragraph about the filming of the movie could have been used to establish a sense of dread about why the last owners were in such a hurry to leave, and thus actually build some tension. Stine Writing 101: “No tension. If there has to be tension, though, make sure to diffuse it immediately before the kid reading the book actually feels anything.”

The inventory is a fun touch, though it’s impossible to tell which items will actually be useful to you. Inventories, skills, etc work well in books like Way of the Tiger, where some techniques may prove more useful than others: as a ninja I’m less likely to have to play dead than I am to escape some bindings, but there are scenarios where both can be used to get out of trouble without necessarily being essential to completing the adventure. Here only certain items will get you to the end, and the rest will pretty much get you killed.

I don’t mind the occasional bogus item. Usually you can tell it’s probably not gonna be useful. I wasn’t surprised while reading one of the Super Mario gamebooks when Luigi’s acquisition of an anchor proved unhelpful, and in fact detrimental, especially when trying to make a death-defying leap with fifty pounds of iron in his back pocket. So my first time through One Night in Payne House I chose the baseball bat, the flashlight, and the cassette recorder. My logic was that I might need to bash something, see in the dark, and/or leave a recording as a distraction while I sneak away.

Turns out baseball bat vs Pom-Pom dog = death, but handful of pebbles vs Pom-Pom dog = dead Pom-Pom dog. Go figure.

In short, it’s an annoying narrative with choices based on luck rather than logic (except the one where I opt not to enter the room with the giggling kids, ‘cos that’s never a good sign in a haunted house) and only one way to the proper ending. Even if you’re looking for something on the zany side, I can’t recommend One Night in Payne House on the basis that the narrator never shuts up about how current events relate to the movie, and how it sucks any sense of surprise or engagement out of the story. There have to be better books in this series than this “highly recommended” one.

As an addendum, I recently began to rethink my criticism of R L Stine after re-reading some childhood favorites. I’m not immune to nostalgia, but I’m better than most at viewing things objectively. So I began to wonder if maybe my issues with Goosebumps and Stine’s work in general has to do with the age and reading level of his audience. I haven’t read his thrillers for older kids, so I can’t comment on those, but I wouldn’t be surprised if he used the same writing philosophy. So do his Goosebumps books come off so babyfied because he’s writing for really young kids? I had a fifth grade reading ability in first grade. Did that shape my opinion of these books?

Actually, no, because he had contemporaries in the late 80s and early 90s for the same age group as his own audience who didn’t pull punches. The best example is Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. Every story in that series is written in the same bare-bones middle-grade-fiction manner as Goosebumps. Obviously reading them as an adult will leave you less satisfied because there isn’t much substance there. Most of the stories in Scary Stories are only a page and a half long at most.

The big difference isn’t the age group or reading level, but the writing philosophy. Stine simply doesn’t want to scare his readers. In One Night in Payne House he has several situations that are objectively terrifying. I hear kids laughing and playing in a room, decide to go in and see what’s up, and find a room full of giggling children…with no heads. Or I’m exploring a dark, haunted house with my best pal at my side, turn back after a long silence, and find he’s gone. Just vanished with neither a trace nor a sound, and now I’m alone in the house with no way out.

Likewise Scary Stories has tales about a man who offers to carry a stranger’s basket, only to find the stranger’s severed head is in the basket, which proceeds to laugh and chase him. Or the infamous story about Harold, the scarecrow who gradually comes to life out of nothing more than impatience at his creators’ constant abuse. All of these are scary concepts.

It’s how Stine chooses to handle them that’s the problem. He pulls the teeth out of every scary moment by slipping “Yikes” and “Uh oh” and “Yuck” into the narrative during the scary moments, and in the cases of his gamebooks, cracks corny jokes every time you die, going as far as breaking the fourth wall on a regular basis. Scary Stories has one short yarn about a woman who gets on the subway, and watches three men board shortly after: two on either side of a friend who is apparently drunk and keeps staring at her. The two “sober” friends take turns getting off at different stops, bidding their drunk pal goodbye as they go, so now it’s just the lone woman on the train with this drunk, wobbling, staring idiot sitting right across from her. When the train takes a sharp turn, the man pitches onto the floor, his hat comes off, and the woman sees he has a bullet hole in his temple.

Now let’s rephrase that last sentence in the Stine style:

When the train takes a sharp turn, the man pitches onto the floor, his hat comes off. Yuck! The woman sees he has a bullet hole in his temple! Talk about a migraine!

Books like Scary Stories tell it straight. Goosebumps‘s intentions are clear as mud. “Reader beware, you’re in for a scare…but also no scares allowed. Have a balloon! Nyuk nyuk!” I’d like to imagine his books for older kids aren’t like this, and maybe I’ll crack a few open one day.

I come off snarky, but I don’t mean any ill will toward Stine, himself. I’m glad his books got more kids to read, especially young boys who tend toward nonfiction stuff at that age. I just don’t agree with his approach at all. I think if you’re gonna write genre stories for kids, they should actually be true to the genre. If you’re a scary author for kids, write stories that are scary. That’s what I was looking for at that age. I suffered inexplicable recurring nightmares from ages five to ten, and reading scary stuff was not only a natural evolution in my personal interests, but also catharsis for the scary things I’d gone to bed with for years. Having it dumbed down felt insulting to my intelligence, and still does. If I find more scares in a one-page story from Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark than in your entire book, I think you need to take a different approach.

Or at least change “you’re in for a scare” to “you’re in for a spooky good time” or something that’s accurate to the content. An invisible kid causing mischief isn’t scary. A basket-head lady sure is, though.

Time for bed. Uncle Mac out.